Making the Poor Pay

As the van inches along a washboard road, you peer through its tinted windows and stare at the many faces looking back without showing yours. Kids are playing soccer, most of the men are away at work, and everyone else is busy with the business of life. They are washing clothes in the creek that bisects the community, collecting and carrying bundles of wood, bathing in buckets of water, and preparing for the next and maybe the first and only meal of the day.

The van comes to a stop. You get out and open your backpack to do a quick inventory: water bottle, cell phone, camera, and hand sanitizer. You take your scheduled does of Malarone. And, double-fisting two aerosol cans, you envelope yourself in a cloud of SPF 50+ sunscreen and Deep Woods Insect Repellent. Stepping out of the mist you re-tie your hiking boots, put on your sunglasses and adjust your wide brimmed hat. You are ready to negotiate. You are ready to create a market for good.

You begin trekking towards the tower that carries electricity over but not into the community. The reply to your personal ad looking for a poor person indicated that she lived in the second row, three houses down from the tower. Your driver/interpreter struggles to keep pace with you.

At the designated location, you find a makeshift shelter with a tattered sheet covering the doorway. You knock on the door frame. The person you have come to see pulls back the sheet and smiles. You catch a glimpse of two little ones fast asleep. They are wrapped in blankets and laying on a dirt floor. “Uno momento” she says. She ducks back inside and appears again with three broken but still functional plastic chairs. She sets them up around a table just outside her doorway.

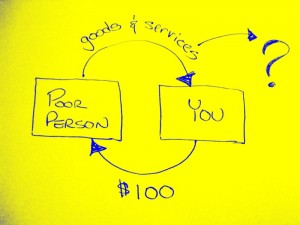

You take a seat at one end. She takes a seat at the other end. Your driver/interpreter takes the third seat. From one of the many pockets of your cargo pants, you pull out $100 worth of local currency. You count it out, stack it neatly, slip it into an envelope, and place it on the table in front of you. Out of the billions of poor people who answered your personal ad you chose her. She promised to use the $100 to send her kids to school.

From another pocket, you take out a pencil and some paper. You give her a quick glance, begin writing, pause, give her another glance, erase, and write down your price.

5 hugs, many smiles, two kisses on the cheek, the chance to play with your kids, meet your neighbors, share lunch and dinner, and participate in a customary dance.

You fold up the paper and pass it to your interpreter. He gives it a quick read, leans over and whispers your price into her ear. Steely-eyed and without any emotion, she instructs him to make some changes. He does and passes her counter-offer back to you.

35 hugs, many smiles, 1two kisses on the cheek, the chance to play with her kids, meet her neighbors, and share lunch and dinner, and participate in a customary dance.

Truth be told, you are a bit disappointed. You have traveled so far to meet her. You have withstood unbelievable humidity, high temperatures, mosquitoes, and limited access to bathrooms. On top of it all, you got diarrhea. And, after taking some Cipro, you are now constipated. You have endured a lot.

After regaining your composure, you reply to her counter-offer.

35 hugs, many smiles, 1two kisses on the cheeck, the chance to play with her kids, meet her neighbors, share lunch and dinner, and participate in a customary dance, and one photograph of her holding a sign saying “Thank You”.

You pass it back to your interpreter. He notes the changes. She nods her head in approval. You reciprocate. With the terms of trade settled, you slide the envelope of cash across the table. She picks it up and begins preparing for lunch.

Lunch is served, you meet the neighbors, get your hugs and the picture. In the van, you whip out your hand sanitizer and offer some to your driver. He declines. You squirt a dollop into your palm, rub your hands vigorously and with a smile say “aeropuerto, por favor.”

In the market for good, getting to a mutually agreeable terms of trade is difficult. It takes time, energy and in many cases the assistance of an interpreter. It can be miscalculated. You may ask for too much. The price they offer you may be too low. Frustrated, one of you or both of you may end up walking away. In either case, you both lose out on an exchange that is mutually beneficial.

Ultimately, the terms of trade will be determined by your relative bargaining strengths. You come from a position of strength. You have more disposable income than your exchange partner. Your desire to help the poor is strong but more than likely not as strong as their desire to receive $100. There are billions of poor people. There are only so many do-gooders. Finding another poor person willing and able to pay the right price for your $100 is relatively easy. For a poor person, gaining access to another do-gooder may not be.

What other variables do you think influence the terms of trade? Your religious background? Your political affiliation?

At what point, if any at all, does a poor person say enough is enough and ask you to leave?

I am sure the poor get together to share notes about their experience with do-gooders. I imagine they talk about the goods and services we prefer, how to give us just enough but not too much, and how to keep us coming back.

What do you think?

What price would you charge a poor person for access to $100?

+++++

If you enjoyed this blog, you may enjoy my This is the Work newsletter.

Thanks. – shawn

P.S. Read the Sidekick Manifesto and Take the Pledge!

+++++

Other posts in the Do-Goodernomics Series:

Post #1: Do-Goodernomics

Post #2: FS DOGUDR ISO PR PERSON

Post #3: Making the Poor Pay

Post #4: Poor Paternalism